Understanding the Heart Attack: A Comprehensive Guide

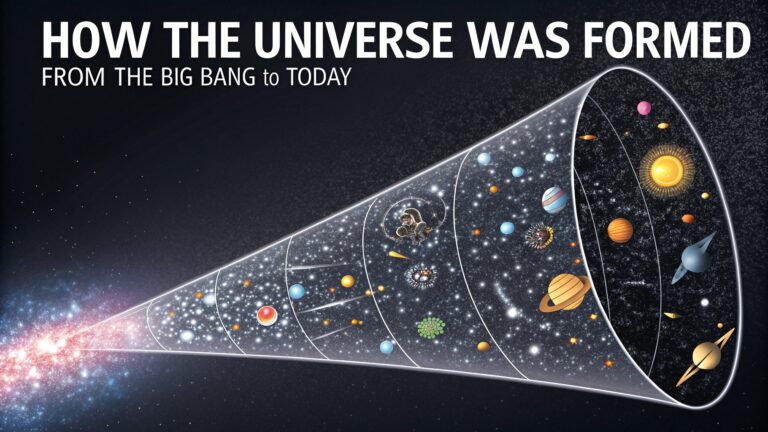

A heart attack, medically known as a myocardial infarction, represents one of the most critical medical emergencies a person can face. It occurs when the flow of oxygen-rich blood to a section of the heart muscle becomes abruptly blocked, most often by a blood clot. If this blood flow is not restored rapidly, the section of heart muscle begins to die from oxygen starvation. This event is not just a singular health crisis but a life-altering moment that underscores the vital importance of cardiovascular health. The pathophysiology of a heart attack typically begins with atherosclerosis, a condition where coronary arteries, the vital vessels supplying the heart with blood, become narrowed and hardened due to the buildup of fatty deposits called plaques. These plaques are composed of cholesterol, fatty substances, cellular waste products, calcium, and fibrin. Over many years, these plaques can remain stable, but they can also become vulnerable, developing a thin, fragile cap that can rupture. When a rupture occurs, the body perceives it as an injury and rushes to form a blood clot (thrombus) to seal it. Unfortunately, this clot can often be large enough to completely occlude the already-narrowed artery, halting blood flow and triggering the catastrophic event we know as a heart attack.

Recognizing the Signs: Symptoms Beyond Chest Pain

The classic Hollywood depiction of a heart attack—a person, usually a man, clutching his chest in dramatic agony—is only one possible presentation, and this stereotype can be dangerously misleading. While severe, crushing chest pain, pressure, or a sensation of squeezing (often described as “an elephant sitting on my chest”) is a common symptom, the reality is far more nuanced. The symptoms of a heart attack can vary significantly between individuals and between men and women. It is crucial to understand that a heart attack can manifest through a constellation of signs, including pain or discomfort in other areas of the upper body, such as one or both arms, the back, neck, jaw, or stomach. Shortness of breath is another cardinal symptom, which can occur with or without chest pain. This may feel like an inability to catch one’s breath even while at rest. Other warning signs include breaking out in a cold sweat, experiencing sudden nausea or vomiting, and feeling lightheaded or dizzy. Particularly in women, symptoms can be subtler, often presenting as extreme fatigue, indigestion-like discomfort, or a general feeling of unwellness. The key takeaway is that any sudden, unexplained, and severe symptom from the neck up and the belly button up should be taken seriously. Time is muscle; every minute of delay results in more irreversible damage to the heart muscle, increasing the risk of long-term complications like heart failure or death.

Immediate Response: The Critical First Hours

Upon suspecting a heart attack, the single most important action is to immediately call emergency medical services (like 911 in the United States). Do not drive yourself or the patient to the hospital. Emergency medical technicians (EMTs) can begin life-saving treatment the moment they arrive, such as administering oxygen, aspirin to thin the blood and prevent further clotting, and nitroglycerin to help improve blood flow. They are also trained to manage cardiac arrest, a common complication of a severe heart attack, with defibrillation and advanced life support. Upon arrival at the hospital, the medical team will work swiftly to confirm the diagnosis using an electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG) and blood tests that measure cardiac enzymes like troponin, which are released into the bloodstream when the heart muscle is damaged. The primary goal of treatment is to restore blood flow as quickly as possible. This is most effectively achieved through an emergency procedure called percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or angioplasty with stenting. In this procedure, a interventional cardiologist threads a thin catheter through an artery, usually in the wrist or groin, to the blocked coronary artery. A tiny balloon is inflated to compress the plaque and open the artery, and a small mesh tube called a stent is permanently placed to keep the artery propped open. If a PCI-capable hospital is not immediately accessible, doctors may administer thrombolytic (clot-busting) drugs to dissolve the obstructive clot. The success of these interventions is heavily dependent on speed, highlighting why recognizing the signs of a heart attack and acting without hesitation is a matter of life and death.

Risk Factors and Prevention: Building a Heart-Healthy Life

While a heart attack can sometimes feel like a sudden, unpredictable event, it is almost always the culmination of years, even decades, of underlying risk factors. Understanding and modifying these risks is the cornerstone of prevention. Risk factors are divided into two categories: non-modifiable and modifiable. Non-modifiable factors include age (risk increases for men over 45 and women over 55), family history of early heart disease, and gender (men are generally at higher risk, though a woman’s risk increases after menopause). However, the power lies in addressing the modifiable risk factors. These include smoking, which damages the lining of arteries and promotes plaque formation; high blood pressure, which forces the heart to work harder; high levels of LDL (“bad”) cholesterol, which contributes directly to plaque; uncontrolled diabetes, which damages blood vessels and nerves; being overweight or obese; and living a sedentary lifestyle. A heart-healthy diet, often exemplified by the Mediterranean diet—rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats while low in sodium, saturated fats, and refined sugars—is profoundly protective. Regular physical activity, aiming for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week, strengthens the heart muscle, improves circulation, and helps manage weight and blood pressure. Furthermore, managing stress through techniques like meditation, yoga, or mindfulness is increasingly recognized as vital for cardiovascular health. For some individuals with very high risk or existing conditions, doctors may also prescribe preventive medications like statins to control cholesterol or low-dose aspirin to prevent clotting. Ultimately, preventing a heart attack is a lifelong commitment to conscious, healthy choices that protect the body’s most vital organ.

Life After a Heart Attack: Rehabilitation and Recovery

Surviving a heart attack is the first step in a new chapter focused on recovery and preventing a future event. This process is formally guided by cardiac rehabilitation, a medically supervised program designed to improve cardiovascular health. Cardiac rehab typically includes three core components: exercise counseling and training to safely strengthen the heart and body; education on heart-healthy living, including nutritional guidance; and counseling to reduce stress and improve mental health. The psychological impact of a heart attack is profound and often under-addressed. Many survivors experience fear, anxiety, and depression, worried about triggering another event. This emotional toll is a critical part of the recovery process and is actively managed within a good rehab program. Adherence to prescribed medications is non-negotiable; these often include antiplatelets (like aspirin or clopidogrel) to prevent clots, beta-blockers to reduce heart rate and blood pressure, ACE inhibitors to ease the heart’s workload, and statins to control cholesterol. The lifestyle changes adopted during recovery—quitting smoking, improving diet, exercising regularly—must become permanent. A heart attack is a stark warning, but it is also a second chance. It provides a clear impetus to embrace a healthier lifestyle, closely monitored by healthcare professionals, to ensure a longer, stronger, and more vibrant life, proving that the aftermath of a cardiac event can be the beginning of a renewed focus on well-being.